Originally

it was a block of marble, an enormous block of white

marble, belonging to the Opera del Duomo of Florence,

excavated with the intention of carving out a giant: a

David or a Prophet for one of the buttresses of the

Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. Initially the work

was entrusted to the sculptor Agostino di Duccio (1462)

and later to Antonio Rossellino (1476) but both were

forced to give up in face of the enormous technical

difficulties. The block of marble was not compact, it was

riddled with veins and above all it was tall and narrow,

more suitable for slender gothic statues than for the

muscular active representations of Renaissance heroes.

Leonardo da Vinci was also approached, and although he

had a considerable experience in bronze sculpture, the

artistic genius declined the offer and the roughly hewn

block of marble was courtyard of the Originally

it was a block of marble, an enormous block of white

marble, belonging to the Opera del Duomo of Florence,

excavated with the intention of carving out a giant: a

David or a Prophet for one of the buttresses of the

Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. Initially the work

was entrusted to the sculptor Agostino di Duccio (1462)

and later to Antonio Rossellino (1476) but both were

forced to give up in face of the enormous technical

difficulties. The block of marble was not compact, it was

riddled with veins and above all it was tall and narrow,

more suitable for slender gothic statues than for the

muscular active representations of Renaissance heroes.

Leonardo da Vinci was also approached, and although he

had a considerable experience in bronze sculpture, the

artistic genius declined the offer and the roughly hewn

block of marble was courtyard of the  forgotten in the Opera del Duomo

until 1501. These were crucial years for the Florentine

Republic. The Medici family had been expelled (1494) and

the gonfalonier Pier Soderini was recalling the artists

to give new impetus and backing to his government and to

further the intellectual and artistic revival of the

city. Michelangelo, informed by friends of the

possibility of acquiring the great abandoned block of

marble, also came back. For him, naturally obstinate,

this opportunity of measuring himself against a

generation of sculptors who had failed, together with the

difficulties created by the previous "mutilations

and damage", must have constituted a particularly

intriguing challenge. Michelangelo was officially

commissioned on 16 August 1501 at the age of 26. The

enterprise took off immediately, and at the beginning of

September the artist began testing the the block. In forgotten in the Opera del Duomo

until 1501. These were crucial years for the Florentine

Republic. The Medici family had been expelled (1494) and

the gonfalonier Pier Soderini was recalling the artists

to give new impetus and backing to his government and to

further the intellectual and artistic revival of the

city. Michelangelo, informed by friends of the

possibility of acquiring the great abandoned block of

marble, also came back. For him, naturally obstinate,

this opportunity of measuring himself against a

generation of sculptors who had failed, together with the

difficulties created by the previous "mutilations

and damage", must have constituted a particularly

intriguing challenge. Michelangelo was officially

commissioned on 16 August 1501 at the age of 26. The

enterprise took off immediately, and at the beginning of

September the artist began testing the the block. In  solidity and quality of October

he had a "turata di tavole" built around it, a

kind of enclosure made of wood and masonry to protect and

conceal his work. He must have made rapid progress since

on 25 January 1504, after little more than two years, the

enormous David was practically complete. solidity and quality of October

he had a "turata di tavole" built around it, a

kind of enclosure made of wood and masonry to protect and

conceal his work. He must have made rapid progress since

on 25 January 1504, after little more than two years, the

enormous David was practically complete.The work

inspired considerable curiosity and admiration among the

citizens, while to the artistic community which had known

the original marble it seemed like "one raised from

the dead". But the statue also kindled envy and

criticism, and was from the very start the target of

fanaticism and vandalism. In the biography devoted to

Michelangelo, Giorgio Vasari relates how Pier Soderini,

while on the whole full of praise for the statue,

considered the nose too big. Pretending to heed him and

to want to re-chisel the nose, the sculptor climbed onto

the scaffolding  judiciously

scattering some marble dust which he had hidden in his

fist. Only then did the gonfalonier grant his definitive

approval, and, "as recompense", four hundred

scudos. Given the exceptional nature of the work, a

lively debate arose about its most suitable location: it

was unthinkable to sacrifice this superb nude, moulded so

as to be appreciated in the round, by flattening it

against a wall, even if it were the wall of the imposing

Duomo of Florence. A committee of the most famous artists

of the time was therefore appointed. Giuliano da the now

elderly Leonardo da Vinci suggested setting the statue up

in the Sangallo and Loggia della the back wall darkened

to enhance the whiteness of the marble. This Signoria,

with solution, consistent with Leonardo’s own

studies of atmosphere and subtle shading was not,

however; consistent with Michelangelo’s ideas. His

David was vibrant judiciously

scattering some marble dust which he had hidden in his

fist. Only then did the gonfalonier grant his definitive

approval, and, "as recompense", four hundred

scudos. Given the exceptional nature of the work, a

lively debate arose about its most suitable location: it

was unthinkable to sacrifice this superb nude, moulded so

as to be appreciated in the round, by flattening it

against a wall, even if it were the wall of the imposing

Duomo of Florence. A committee of the most famous artists

of the time was therefore appointed. Giuliano da the now

elderly Leonardo da Vinci suggested setting the statue up

in the Sangallo and Loggia della the back wall darkened

to enhance the whiteness of the marble. This Signoria,

with solution, consistent with Leonardo’s own

studies of atmosphere and subtle shading was not,

however; consistent with Michelangelo’s ideas. His

David was vibrant  with a

life of his own, and could certainly not be adapted for

insertion in a "niche, blackened behind like some

miserable chapel". Michelangelo was not present at

the discussion but his desire, voiced by the herald of

the Signoria, was to place his "giant"

– as the Florentines called it - in front

of the Palazzo della Signoria, the civic heart of the

city, or at most in the courtyard of the Palazzo itself.

The choice fell to the front of the Palazzo beside the

great doorway: the severe rusticated facade would

admirably set off the physical vitality of the David

plastically defined in the white marble. with a

life of his own, and could certainly not be adapted for

insertion in a "niche, blackened behind like some

miserable chapel". Michelangelo was not present at

the discussion but his desire, voiced by the herald of

the Signoria, was to place his "giant"

– as the Florentines called it - in front

of the Palazzo della Signoria, the civic heart of the

city, or at most in the courtyard of the Palazzo itself.

The choice fell to the front of the Palazzo beside the

great doorway: the severe rusticated facade would

admirably set off the physical vitality of the David

plastically defined in the white marble.

It was no easy matter to transport the heavy statue,

which was more than four metres high, to Piazza Signoria,

passing through the narrow and tortuous streets of

Florence. Michelangelo and some of his ingenious friends

designed and built a special "castle" with

winches and sturdy ropes  for the

purpose. The journey took four days and to avoid acts of

vandalism the statue was policed night and day by special

guards; in spite of this it was the target of

stone-throwing on the part of certain young louts (sadly,

history repeats itself) who paid for their disrespect

with a week of prison. On 8 June 1504 the

"giant" reached the steps of the Palazzo della

Signoria, but it was not raised onto its marble base and

presented to the Florentines until 8 September; the feast

of Our Lady. The crowd gathered in the square was

impressed by the beauty of the colossal nude, but also by

the iconographic originality. The Davids sculpted up

until then had been generally inspired by the Biblical

text, figures of young men clothed in tunics or drapery.

A previous illustrious nude was Donatello’s bronze

(now in the Bargello Museum), but with a delicately

adolescent body, adorned in the ancient manner with

sandals, for the

purpose. The journey took four days and to avoid acts of

vandalism the statue was policed night and day by special

guards; in spite of this it was the target of

stone-throwing on the part of certain young louts (sadly,

history repeats itself) who paid for their disrespect

with a week of prison. On 8 June 1504 the

"giant" reached the steps of the Palazzo della

Signoria, but it was not raised onto its marble base and

presented to the Florentines until 8 September; the feast

of Our Lady. The crowd gathered in the square was

impressed by the beauty of the colossal nude, but also by

the iconographic originality. The Davids sculpted up

until then had been generally inspired by the Biblical

text, figures of young men clothed in tunics or drapery.

A previous illustrious nude was Donatello’s bronze

(now in the Bargello Museum), but with a delicately

adolescent body, adorned in the ancient manner with

sandals,  sword and helmet. All

the Davids had, however, been instructively represented

with the macabre trophy of the severed head of Goliath at

their feet. Michelangelo had instead conceived the image

of a vigorous man, totally naked like an ancient hero or

athlete with a glance which reveals a profound confidence

in his own capacity. Because of his demonstrable physical

and moral force, the David immediately came to embody in

the imagination of the Florentines a symbol of civil

virtue and a warning for the enemies of freedom.

Subsequently even the academics have almost unanimously

affirmed this civic quality in the David, while advancing

different interpretations. Some have found links with the

thought of Dante, others with the sermons of Savonarola,

yet others with Neoplatonic thought. Most compelling is

the theory which sees the "giant" uniting sword and helmet. All

the Davids had, however, been instructively represented

with the macabre trophy of the severed head of Goliath at

their feet. Michelangelo had instead conceived the image

of a vigorous man, totally naked like an ancient hero or

athlete with a glance which reveals a profound confidence

in his own capacity. Because of his demonstrable physical

and moral force, the David immediately came to embody in

the imagination of the Florentines a symbol of civil

virtue and a warning for the enemies of freedom.

Subsequently even the academics have almost unanimously

affirmed this civic quality in the David, while advancing

different interpretations. Some have found links with the

thought of Dante, others with the sermons of Savonarola,

yet others with Neoplatonic thought. Most compelling is

the theory which sees the "giant" uniting  within himself the qualities of

David, the heroic biblical defender of the faith and of

justice, and those of the figure of Hercules in classical

mythology, symbol of strength sustained by intelligence. within himself the qualities of

David, the heroic biblical defender of the faith and of

justice, and those of the figure of Hercules in classical

mythology, symbol of strength sustained by intelligence.

After an act of vandalism which the statue suffered in

1527, Duke Cosimo I had it restored in 1543. Considering

the civic significance of the statue, it might seem

strange that the very monarch who had suppressed or

undermined the power of the democratic institutions of

the Republic contributed to its restoration. The

duke’s gesture, as well as expressing a sincere

appreciation of Michelangelo, was an integral part of his

political strategy. The figure of Hercules had been

exalted since the times of Lorenzo il Magnifico, and

Cosimo himself had more than once compared the acts of

his government to the "Labours" of the mythical

hero. He did not therefore attempt to distance the David

from the palace,  which

had in the meantime become his residence; on the contrary

in ordering its restoration he put himself forward as the

ideal restorer of civil peace. His ambiguity is revealed

in his ordering of other colossi to place alongside it in

the attempt to dilute its presence. which

had in the meantime become his residence; on the contrary

in ordering its restoration he put himself forward as the

ideal restorer of civil peace. His ambiguity is revealed

in his ordering of other colossi to place alongside it in

the attempt to dilute its presence.

Exposed to the elements for centuries, by the mid

nineteenth century the fragile and porous marble of the

David was considerably deteriorated. In view of the

fourth centenary of the artist’s birth, it was

decided to remove the work to the Accademia delle Belle

Arti. In 1882 it was placed within a covered

neo-Renaissance style tribune designed by the architect

De Fabris, while a replica made by the copyist Arrighetti

was put in its original position in Piazza Signoria. The

removal to the Museum had the result of confirming its

superiority in comparison to other statues, and, although

abstracted from the civic environment,  it undoubtedly gained in terms

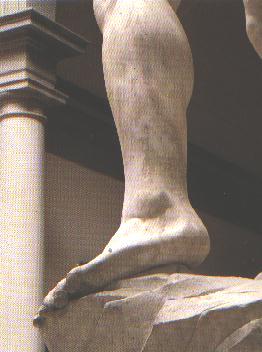

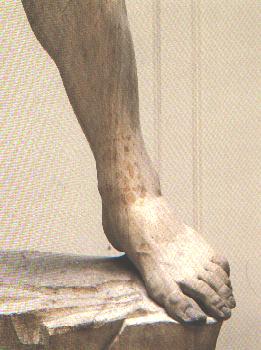

of fame. An act of vandalism on the part of a maniac in

September 1991, who attacked the toes of the left foot

with a hammer; is an extreme example of the cult, or

worse, of fanaticism which has grown up around the David.

By now well rooted in the collective imagination as an

ideal of perfection, Michelangelo’s David is the

best-known sculpture in the world, a symbol of the art of

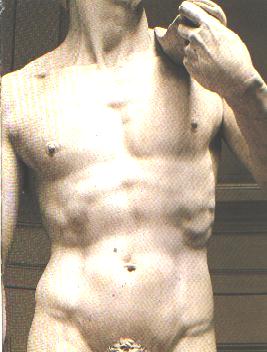

all time. The first impression is that of a colossal

naked body of an ancient athlete, or of a classically

designed pagan god, perfect in anatomical form and proud

of glance. But we must not stop at this first appearance;

we must approach the work gradually, slowly circling it

to discover from a multitude of angles, the many men,

heroes and myths that it contains. The sculpture we have

in front of us does not show a youth in a static, relaxed

and triumphant pose, it undoubtedly gained in terms

of fame. An act of vandalism on the part of a maniac in

September 1991, who attacked the toes of the left foot

with a hammer; is an extreme example of the cult, or

worse, of fanaticism which has grown up around the David.

By now well rooted in the collective imagination as an

ideal of perfection, Michelangelo’s David is the

best-known sculpture in the world, a symbol of the art of

all time. The first impression is that of a colossal

naked body of an ancient athlete, or of a classically

designed pagan god, perfect in anatomical form and proud

of glance. But we must not stop at this first appearance;

we must approach the work gradually, slowly circling it

to discover from a multitude of angles, the many men,

heroes and myths that it contains. The sculpture we have

in front of us does not show a youth in a static, relaxed

and triumphant pose,  nor a

warrior caught in the strain of battle, as he was wont to

be described with anatomical virtuosity in the second

half of the fifteenth century. David, the young Jewish

shepherd is for Michelangelo an already mature man, and

the artist depicts him in the moment before the launching

of the stone with which he is to strike the Philistine

giant, at a climax of mental concentration and physical

tension. If, without embarrassment, we try to imitate his

posture, and with legs slightly apart put our weight on

the right, the left knee flexes forwards almost

automatically, creating an attitude of

"reflection" which raises the left shoulder and

the right buttock. Up to this point the body remains

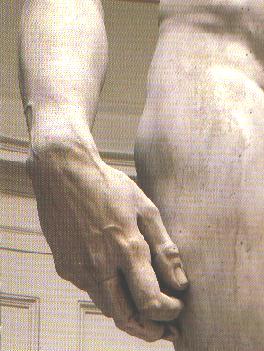

balanced. Now let’s pretend that we are grasping the

sling (a catapult with a leather band) which is resting

on our shoulder, in our left hand, and gripping a stone

in our right, the wrist tensely nor a

warrior caught in the strain of battle, as he was wont to

be described with anatomical virtuosity in the second

half of the fifteenth century. David, the young Jewish

shepherd is for Michelangelo an already mature man, and

the artist depicts him in the moment before the launching

of the stone with which he is to strike the Philistine

giant, at a climax of mental concentration and physical

tension. If, without embarrassment, we try to imitate his

posture, and with legs slightly apart put our weight on

the right, the left knee flexes forwards almost

automatically, creating an attitude of

"reflection" which raises the left shoulder and

the right buttock. Up to this point the body remains

balanced. Now let’s pretend that we are grasping the

sling (a catapult with a leather band) which is resting

on our shoulder, in our left hand, and gripping a stone

in our right, the wrist tensely  clenched like that of the

statue, and move the left foot forward (as can be clearly

observed from the back view of the statue). This position

cannot be held for more than a moment... there follows

immediately a transfer of weight to the ball of the left

foot, the twisting of the trunk and the launch of the

stone in the direction upon which the figure’s

glance is focused. The head set upon the strained neck is

turned, as if abruptly, towards the left (in medieval

illustration danger always approached from this side).

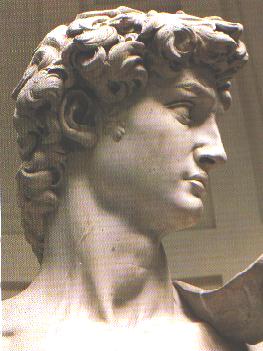

It’s not easy to speak of the beauty of David’s

face. To appreciate his expression we have to circle him

slowly, discovering at each step and from each angle what

he reveals: not a single face, but rather a series of

faces, of increasing intensity. Standing in front of the

statue we see only the classic profile conveying a sense

of thoughtful composure. But when we move around it we

observe how this expression is intensified, clenched like that of the

statue, and move the left foot forward (as can be clearly

observed from the back view of the statue). This position

cannot be held for more than a moment... there follows

immediately a transfer of weight to the ball of the left

foot, the twisting of the trunk and the launch of the

stone in the direction upon which the figure’s

glance is focused. The head set upon the strained neck is

turned, as if abruptly, towards the left (in medieval

illustration danger always approached from this side).

It’s not easy to speak of the beauty of David’s

face. To appreciate his expression we have to circle him

slowly, discovering at each step and from each angle what

he reveals: not a single face, but rather a series of

faces, of increasing intensity. Standing in front of the

statue we see only the classic profile conveying a sense

of thoughtful composure. But when we move around it we

observe how this expression is intensified,  contracted to the point of

menace in the glance directed at the enemy. What we have

before us is not therefore a detached and heroic

attitude, but one that is much more human and intimate.

The very defects contribute to this earthly dimension: as

one gets closer, in fact, David’s head and hands

begin to appear out of proportion. This is an effect

deliberately designed to accentuate those parts of the

body connected with Thought and Action. Had it been

executed according to the classical canons the face would

never have shown the same intensity, and the power of the

hands would have vanished. Although Michelangelo had a

profound knowledge of anatomy, based on his studies of

antiquity and real life observation, he goes beyond

theoretical rules, elaborating and disregarding them to

highlight moral expression. contracted to the point of

menace in the glance directed at the enemy. What we have

before us is not therefore a detached and heroic

attitude, but one that is much more human and intimate.

The very defects contribute to this earthly dimension: as

one gets closer, in fact, David’s head and hands

begin to appear out of proportion. This is an effect

deliberately designed to accentuate those parts of the

body connected with Thought and Action. Had it been

executed according to the classical canons the face would

never have shown the same intensity, and the power of the

hands would have vanished. Although Michelangelo had a

profound knowledge of anatomy, based on his studies of

antiquity and real life observation, he goes beyond

theoretical rules, elaborating and disregarding them to

highlight moral expression.

|

Originally

it was a block of marble, an enormous block of white

marble, belonging to the Opera del Duomo of Florence,

excavated with the intention of carving out a giant: a

David or a Prophet for one of the buttresses of the

Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. Initially the work

was entrusted to the sculptor Agostino di Duccio (1462)

and later to Antonio Rossellino (1476) but both were

forced to give up in face of the enormous technical

difficulties. The block of marble was not compact, it was

riddled with veins and above all it was tall and narrow,

more suitable for slender gothic statues than for the

muscular active representations of Renaissance heroes.

Leonardo da Vinci was also approached, and although he

had a considerable experience in bronze sculpture, the

artistic genius declined the offer and the roughly hewn

block of marble was courtyard of the

Originally

it was a block of marble, an enormous block of white

marble, belonging to the Opera del Duomo of Florence,

excavated with the intention of carving out a giant: a

David or a Prophet for one of the buttresses of the

Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. Initially the work

was entrusted to the sculptor Agostino di Duccio (1462)

and later to Antonio Rossellino (1476) but both were

forced to give up in face of the enormous technical

difficulties. The block of marble was not compact, it was

riddled with veins and above all it was tall and narrow,

more suitable for slender gothic statues than for the

muscular active representations of Renaissance heroes.

Leonardo da Vinci was also approached, and although he

had a considerable experience in bronze sculpture, the

artistic genius declined the offer and the roughly hewn

block of marble was courtyard of the  forgotten in the Opera del Duomo

until 1501. These were crucial years for the Florentine

Republic. The Medici family had been expelled (1494) and

the gonfalonier Pier Soderini was recalling the artists

to give new impetus and backing to his government and to

further the intellectual and artistic revival of the

city. Michelangelo, informed by friends of the

possibility of acquiring the great abandoned block of

marble, also came back. For him, naturally obstinate,

this opportunity of measuring himself against a

generation of sculptors who had failed, together with the

difficulties created by the previous "mutilations

and damage", must have constituted a particularly

intriguing challenge. Michelangelo was officially

commissioned on 16 August 1501 at the age of 26. The

enterprise took off immediately, and at the beginning of

September the artist began testing the the block. In

forgotten in the Opera del Duomo

until 1501. These were crucial years for the Florentine

Republic. The Medici family had been expelled (1494) and

the gonfalonier Pier Soderini was recalling the artists

to give new impetus and backing to his government and to

further the intellectual and artistic revival of the

city. Michelangelo, informed by friends of the

possibility of acquiring the great abandoned block of

marble, also came back. For him, naturally obstinate,

this opportunity of measuring himself against a

generation of sculptors who had failed, together with the

difficulties created by the previous "mutilations

and damage", must have constituted a particularly

intriguing challenge. Michelangelo was officially

commissioned on 16 August 1501 at the age of 26. The

enterprise took off immediately, and at the beginning of

September the artist began testing the the block. In  solidity and quality of October

he had a "turata di tavole" built around it, a

kind of enclosure made of wood and masonry to protect and

conceal his work. He must have made rapid progress since

on 25 January 1504, after little more than two years, the

enormous David was practically complete.

solidity and quality of October

he had a "turata di tavole" built around it, a

kind of enclosure made of wood and masonry to protect and

conceal his work. He must have made rapid progress since

on 25 January 1504, after little more than two years, the

enormous David was practically complete.